Image tweaks are common in the realm of scientific journals — but when do authors cross the line between the acceptable and the fraudulent?

During the 2019 ISMTE North American Conference (in Durham, NC), two experts shared their insights on what constitutes legitimate use of image alteration to beautify graphics in scientific work and what constitutes unethical alteration of these images for the purposes of data manipulation.

In the modern era, with the introduction of digital image editing systems (most notably PhotoShop), improper editing of images has become a significant problem in the publishing arena.

Although the use of such systems has become standard in scientific writing, editors and editorial assistants must be cautious whenever they are handling images that have been altered in any way, shape, or form—otherwise, all too often, improper data manipulation can easily slip through the cracks.

However, because these software systems are used so often, it can be difficult to pinpoint what type of usage is potentially problematic versus what type of usage is not. Because of this, the two speakers discussed specific warning signals to watch for.

One possible red flag is the changing (enhancing, obscuring, moving, removing, or introducing) of one specific feature within an image. This is compared to changing the entire graphic in one of these ways, which is generally permissible.

If the whole image is altered, it is usually for aesthetic purposes, which is most likely not problematic in terms of scientific accuracy. Problems typically arise with an image that has one particular doctored portion.

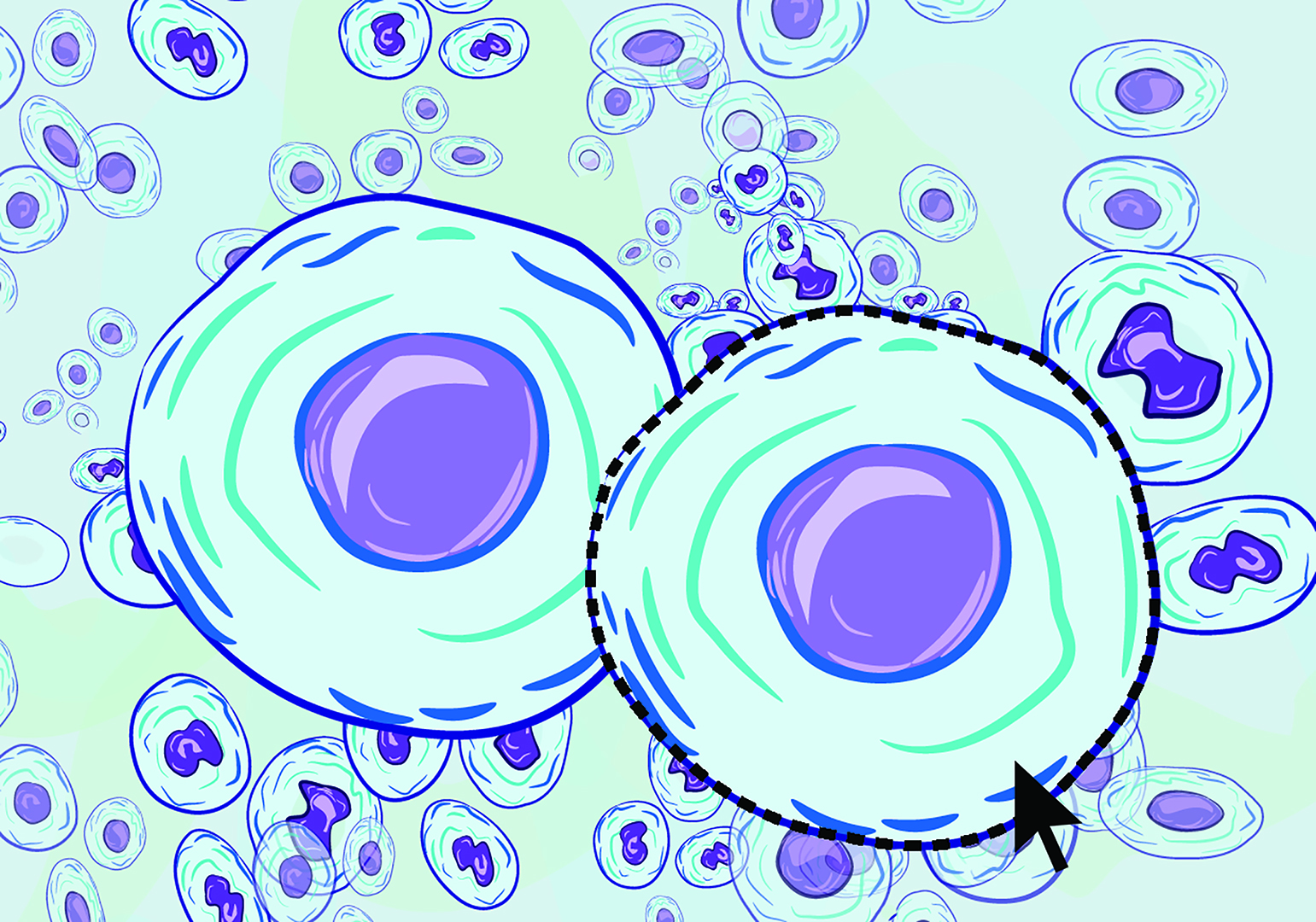

Another potential warning sign is two separate cells in a graphic that are either exactly alike or suspiciously similar to one another. The speakers noted that this is analogous to snowflakes—no two snowflakes will ever be identical. Likewise, in any given graphic, if two separate cells are identical, it’s probably not through natural experimental means.

The discussion also focused on how editorial office staff can appropriately address authors who might be in the wrong; for instance, they might request a verbal explanation and/or an original image/capture for comparison to the edited version. If the authors are unable or unwilling to provide such an original image/capture, the work will likely be disqualified, and other sanctions might also be in order, depending on the severity of the case (and also depending on whether the author’s violations were likely intentional versus unintentional).

Although editorial office staff members might not be directly responsible for determining whether an altered image has been unethically edited, staff members should be prepared to weigh in, should an editor and/or other author ask for an opinion. Moreover, an editorial office worker should be prepared to contact authors to discuss problems with image data manipulation whenever they arise—and, in extreme cases, to inform authors that due to an ethical violation, their work will no longer be considered for publication.

Cutting-edge technology has made image editing much easier, and this has had many positive impacts on the publishing industry. However, it has also allowed authors to much more easily publish images with fraudulent data. As time goes on and technology becomes more advanced, this topic will only become more relevant.